Drive into Sweetwater, Texas, and you’ll pass a welcome sign painted on a wind-turbine blade: “Wind Energy Capital of North America.” Drive further through town, and you hit the flip side of that brag-panel.

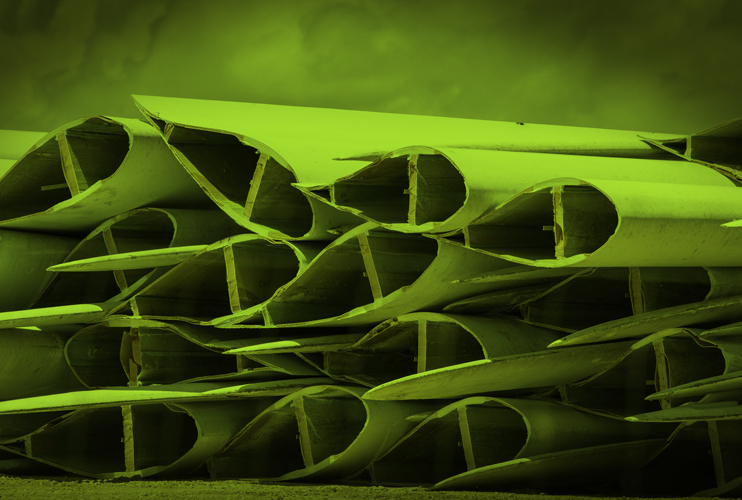

Across from the historic cemetery sits a graveyard of a different kind—turbine blades. Thousands of them. Cut into sections longer than school buses, they blanket approximately 30 acres north of town, and another ~10 acres southward—all tied to a recycling schema that never quite ran. Stagnant water breeds mosquitoes. Rattlesnakes shelter in the shadows. Kids could explore tunnels between stacked blades.

Five hundred miles northeast, in Iowa, three sites played a nearly identical tune. Roughly 1,300 blades sat across three parcels—~868 in Newton at the old Maytag facility; ~400 in Ellsworth; 22 in Atlantic.

These weren’t supposed to become dumps. They were supposed to be recycled. Businesses promised blade-to-pellet transformation. Major companies—General Electric (GE), MidAmerican Energy among them—paid millions. Instead, the blades just piled up.

The Perfect Storm

Three forces converged to create this mess:

- Accelerated repowering.

Beginning in 2016, IRS guidance around the “begin construction” rule and the industry’s 80/20 repowering interpretation enabled many turbines to qualify as newly placed in service—which reset a fresh up-to-10-year Production Tax Credit (PTC). That triggered more blade replacements and younger retirements than expected.

- Materials that won’t quit.

Turbo-blades are built to last—fiberglass composites, thermoset resins. That durability is great in wind; terrible for recycling. You can’t easily melt them like typical plastics. Their strength creates serious disposal headaches. Industry analysts cite ~43 million metric tons of blade waste globally by 2050.

Between those forces, oversight lagged.

The Collapse

Sweetwater, Texas

Blades started arriving in 2017 at Sweetwater sites. By 2020 the county—Nolan County—declared the location a public nuisance.

In 2022 the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) issued an agreed order: the business in question was found storing ~320,010 cubic yards of blades without authorization at one site, and ~128,171 cubic yards at a second, and assessed a penalty of $10,255 (after deferrals) for illegal waste storage. The company defaulted on property taxes, payments lagged. Site fencing was added only after public pressure.

Iowa

The story repeats. In 2017, the same company was contracted by MidAmerican and others to handle thousands of blades. Instead of processing, the blades were warehoused unattended for years. In 2024 the state of Iowa sued the company and its executives for violations of solid-waste law. Meanwhile, cleanup finally began: MidAmerican cleared the Ellsworth site by 2022; GE cleared Newton/Atlantic during 2024 by hiring third-party firms.

GE’s federal complaint is blunt: GE paid the company $16.9 million (~$3,600 per blade) to recycle ~5,000 blades; instead, “[The company] simply stored the blades… where they sat for years,” the suit alleges.

What Failed

Due diligence. Developers and OEMs paid millions without thoroughly vetting operational capacity. No performance bonds sized to cover worst-case removal. Little real oversight post-handoff. Disposal got treated like a procurement item, not a long-tail liability.

Regulatory architecture. There’s no federal mandate specifically for turbine blade disposal. U.S. regulation remains patchwork. States and localities are moving, but slowly. These regulatory gaps let opportunistic firms operate with limited accountability.

Industry blind spots. End-of-life planning was deferred. Recycling standards minimal. Few developers questioned whether the “solution” really existed at scale. Until the blade piles said otherwise.

The Media Damage

When the images of blade stockpiles surfaced—with captions like “Graveyard of the green giants”—they instantly became cause for rural community suspicion, and ammunition for wind-campaign opponents.

What was marketed as clean, sustainable energy began to feel like industrial junk. The optics stung. Communities hosting wind farms felt betrayed: you get turbines, you get tax revenue, but also you get the disposal risk. What the industry didn’t say: every blade eventually needs a home.

What Actually Works

Not all blade recycling is vaporware. Some models are operational and instructive.

Consider REGEN Fiber in Fairfax, Iowa, which uses a patent-pending mechanical process (no heat/chemicals) to recycle blades into fiber reinforcement products for concrete and asphalt. The facility began production in 2024 and initial capacity is ~3,000 blades/year, with potential >30,000 tons/year of shredded blade material.

Or consider cement-kiln and waste-to-energy co-processing. One of the most viable current options is co-processing blades as an alternative fuel and raw material in cement kilns or other high-temperature industrial processes. The blade’s composite resin serves as fuel while the fiberglass provides silica and calcium for the clinker mix—leaving no residual ash. Facilities in the U.S. (through GE and Veolia partnerships) and Europe (notably Holcim’s “Geocycle” program) are already doing this at scale. Capacity remains limited, but it’s a proven, commercially active route that meets both waste-reduction and energy-recovery goals.

Smaller programs have turned blades into pedestrian bridges, playground equipment, and architectural elements. These are creative rather than scalable but can demonstrate circular-economy value to communities.

The real success stories are emerging where these methods overlap—when utilities and manufacturers combine credible processing technology with transparent reporting.

Lessons for Developers

If you’re a wind-farm developer, project lead, or asset manager, here are hard-earned take-aways:

- Contract protection starts with verification. Visit claimed recycling facilities. Check they exist and are operating. Insist on performance bonds large enough to cover full removal cost in a failure scenario. Tie payments to verified processing (weigh tickets, kiln receipts, deconstruction reports)—not just collection or stacking.

- Budget for disposal from Day 0. Integrate realistic disposal cost into your financial models. Don’t assume “blade recycling” will be cheap because someone told you so. Assume hauling, state-line transport, processing premiums.

- Don’t treat disposal as an afterthought. At project conception, pick turbines with lifecycle/disposal in mind. Diversify disposal strategy; avoid reliance on a single vendor. Review contractor financial health, enforcement history. Believe those with rental arrears at their disposal sites have weak risk profiles.

- Communicate with stakeholders. The community hosting your site is watching what you’ll do at wind-end-of-life. Messaging matters. If you don’t tell the story, someone else will—and they’ll show photos of blade mountains.

- Develop competitive advantage. Be early. Contract with verified recyclers, build disposal credibility, use responsible blade management as part of your sustainability and social-license narrative.

The Path Forward

More states are waking up. Extended-producer-responsibility frameworks, landfill bans (or restrictions), stricter bonding and performance-assurance rules are under discussion. The cheap “take your blades and we’ll deal with them later” era is ending.

Standout recyclers are scaling. Disposal costs are trending upward. The credibility gap for wind farms in rural hosting areas is real. If you don’t get ahead of this, you’ll pay—with cash, with permitting delays, with public ire.

Remember: the U.S. has around 73,000–76,000 wind turbines, which implies roughly 220,000+ blades in service. A major retirement/repowering wave is on the horizon.

Conclusion

Sweetwater and Iowa are not outliers; they’re warning lights. These blade fields stand as monuments to inadequate planning, ambiguous contracts, and lax oversight. But they don’t have to be your story.

Smart developers treat blade disposal not as a problem to defer but as a competitive advantage to leverage.

- Build disposal strategy into the project from Day 1.

- Partner with verified recyclers.

- Budget the real cost.

- Be transparent with stakeholders.

- If you let someone else define your end-of-life story, you’ll wake up on a 30-acre blade heap.

At North Coast Enterprise, you know the pattern from water infrastructure, decommissioning risks, long-tail liabilities. Blade disposal is following an identical trajectory: what looks like “far future” is becoming “now.”